Why Can’t MacBooks Be More Like Lego?

by Charles W. Moore

One of the things I think PC makers often do better than Apple is building modularity into their systems. The modular concept isn’t entirely foreign to Apple, and in the context of portables has been incorporated to a greater or lesser degree, with the PowerBook 1400 and PowerBook G3 Series WallStreet and Lombard representing a high water mark in accessibility to internals, and the polar opposite being the G3 and G4 iBooks (all of them) which are a nightmare to service, even for something as mundane as upgrading the hard drive, but user serviceability and upgradability has never been outstanding in any Apple notebook. Consequently, I’ve regarded with envy the ease of swapping hard drives or adding RAM to certain PC laptop models.

I’m a fan of the modular laptop motif, and as it would allow you to custom tailor your ‘Book to satisfy your particular requirements and/or fit your budget, but you wouldn’t be locked into a particular configuration, and could conceivably own the makings of several different configurations to suit different specific tasks. You would also be able to upgrade particular features of your ‘Book without investing in a whole new machine.

There are a number of of aspects I would like to see addressed in the ideal MacBook that are not really functional features, but rather engineering and design policy issues. In a nutshell, I would like my dream MacBook to be both processor upgradeable, and easy to work on for things like RAM and hard drive upgrades, and have a removable device expansion bay for quick and easy drive upgrades and swaps. Another area where there is plenty of room for improvement would be establishing channels to make replacement ‘Book service and repair parts easily and conveniently available (the current status quo is that it is difficult for even authorized Apple service providers to obtain parts!).

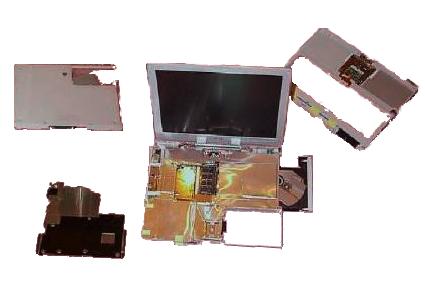

An Apple Service supervisor once remarked to me that computers are just big Lego sets. I like that analogy, but would love to see it extended to a degree that MacBooks were almost as easy to take apart and put together as Lego creations. My ideal ‘Book has plenty of Lego-esque nuances, and I see no logical reason why any notebook, or indeed other types of computers, could not be built to be easy to strip down to their basic component modules. Instead, it so often appears that computers are designed deliberately to make them difficult to take apart and service.

This issue is of course not unique to computer design. Long ago I spent several years earning my living as an auto mechanic, and I remember frequently wondering whether there was a conspiracy among engineers and car designers to make life difficult for service and repair technicians. This has only gotten worse with smaller cars, more technology and features and front-wheel drive that crams the entire drive train into one end of the vehicle. One reason I’m partial to pickup trucks. I guess a computer analogy to smaller autos would be slim, compact notebooks.

As I noted above, Apple has blown hot and cold on the ease of service issue over the years. The old, original, compact Macs were tough to get inside, requiring long Torx screwdrivers and the infamous case splitter. One of Apple’s best ideas was the slide-out motherboards that first appeared the Color Classic, and were continued on the all-in-one 500 series desktop machines, and the 600 series modular Macs. The 7200 and up 7xxx Series Power Macs were also relatively service-friendly, as were the Blue & White and G4 Power Macs, and the Mac Pros are not bad either. On the other hand, the iMac in its various permutations has always been one of the more difficult Macs to open up and work on, so there seems to be little consistency of purpose in this context.

On the PowerBook side, pre 5300/190 PowerBooks were plain hard to work on. With the 5300, Apple somewhat half-heartedly made RAM upgrades a user serviceable procedure (i.e.: upgrading your own RAM would no longer invalidate your warranty). However, opening the 5300 was not exactly convenient, involving acquisition of the proper Torx screwdriver and the delicate removal of the keyboard.

The PowerBook 1400 was a quantum improvement in terms of internal access with its flip-up keyboard, two easily accessible RAM expansion slots, and removable processor daughtercard. The 1400 also proved that engineering limitations are not the main reason for hard-to-work-on PowerBooks - at least full-sized ones - since it shared a lot of the 5300’s motherboard architecture, and was about the same physical size.

Unfortunately, the PowerBook 3400 represented a reversion to the 5300 case motif, and the subnotebook PowerBook 2400 was a truly daunting proposition to open up, requiring the removal of more than 30 small, disparately sized screws.

The G3 series PowerBooks were a mixed blessing user serviceability wise. The keyboard is easy to remove for access, and RAM upgrades are reasonably straightforward, at least for the top slot, as is hard drive replacement on the WallStreet and Lombard. The Pismo was a step backward in hard drive accessibility The Wallstreet/Lombard drive swap procedure is a simple: unscrew a single retaining screw, lift the HD cage up and disconnect the ribbon cable, remove the drive just reverse the process for the new drive. Anyone who isn’t completely ham-fisted should be able to do this procedure

The Pismo OTOH, is involves removing the heat exchanger and CPU daughter card as one unit before you can get at the HD connector (under the CPU). Replacing the drive itself is the easiest part of the process. More challenging is putting it all back together, which requires careful maneuvering to get the CPU + heat exchanger plugged back in.

Also in the G3 series negative column was Apple’s decision to mount the boot ROMs on the processor daughtercard - an apparently deliberate anti-upgrading strategy, which was overcome as upgrade vendors developed workarounds to Apple’s policy refusal to license its ROMs to third-party developers.

However, the G3 Series were light years ahead of any Apple portable that came since in innards accessibility, with the lone and hopeful exception of pretty decent hard drive access in the new MacBook.

“The hard drive in the iBook is not end-user, or even dealer/service center, upgradeable. Just accessing the hard drive bay is a job involving the removal of over two-dozen screws, hex-nuts, plastic parts, and very small, sensitive, electronic components. If the proper level of anti-static protection is not maintained and the take-apart procedure not properly documented then a successful upgrade is nearly impossible.” Sigh. To bone up on what’s involved in tearing down and servicing most Apple notebooks back to the G3 WallStreet and clamshell iBook, check out the excellent and free illustrated take-apart guides posted by iFixIt.com.

I’m not holding my breath waiting for a modular, easy to disassemble, conveniently processor upgradeable PowerBook. While I think there would be a ready market for a mix-and-match ‘Book, I doubt that a much higher percentage of laptop buyers give any thought to ease of service issues when choosing a computer than most people do when shopping for an automobile.

Apple’s hostility to third-party upgrades is well known. They want to sell you upgrades themselves every couple or three years, but with a new computer wrapped around them. My own Pismo PowerBook, which will be seven years old this year and is still in daily use, is an example of how upgradability and expandability work against that business model. If I hadn’t been able to upgrade the processor and install a higher-capacity, faster hard drive and a DVD-burning SuperDrive in place of the original DVD-ROM drive, the Pismo would probably have been long-since retired or handed off to another family member.

Consequently, I doubt there is much realistic hope of there being another ‘Book as easy to work on and upgrade as the PowerBook G3 Series and 1400 unless significant consumer pressure can be brought to bear, and I don’t anticipate that happening, at least until the computer market matures more than it has up to now.

Eventually perhaps, consumers will get tired of buying computers that cost one or two or three thousand dollars and then go obsolete within two years with no upgrade path We simply wouldn’t put up with it in any other consumer appliance in this price range. The U.S. auto industry used to count on planned obsolescence bringing customers back to the showroom every two years or so. Then the Japanese and Koreans showed up with their cars that would run reliably for many years and didn’t go out of style every September, and an ethos of finding out what consumers really wanted and trying to accommodate them.

Ultimately, U.S. automakers had to follow suit or face diminution, if not extinction, and that is still an imponderable. The old annual styling change with little engineering innovation didn’t cut it anymore.

Of course, computers and cars make a rough analogy at best, especially pertaining to Apple, which has no competition in the Mac market. However, I think that as the personal computer market matures and becomes more commodified, consumers may demand greater long-term value from their investment, and enhanced functionality instead of just styling gimmicks and speed increases. Maybe then we will see a modular MacBook.

Note: Letters to PowerBook Mystique Mailbag may or may not be published at the editor's discretion. Correspondents' email addresses will NOT be published unless the correspondent specifically requests publication. Letters may be edited for length and/or context.

Opinions expressed in postings to PowerBook Mystique MailBag are owned by the respective correspondents and not necessarily shared or endorsed by the Editor and/or PowerBook Central management.

If you would prefer that your message not appear in PowerBook Mystique Mailbag, we would still like to hear from you. Just clearly mark your message "NOT FOR PUBLICATION," and it will not be published.

CM