Mac Notebook Evolution; A Desktop Replacement Memoir – The ‘Book Mystique

More often than not right from the beginning, Apple’s Macs have tended to skew toward small. The original Macs were called “compacts,”, and notwithstanding a few exceptions like the honking Big Mac II FX, the 68k and PowerPC desktop tower machines, and the 3400c/3500 PowerBooks and 17-inch PowerBooks/MacBook Pros, the most imaginative and memorable Macs over the years have been the smaller ones — those original 9-inch Classic Macs and the 10-inch Color Classic, the Power Max G4 Cube, and the Mac mini; and in the portable category the original PowerBook 100, the PowerBook Duo, PowerBook 2400c, the 13-inch aluminum MacBook and MacBook Pro, and of course the two generations and three sizes of MacBook Air.

Then of course the iPad, which has frequently impressed me as being very much in the tradition of those original compact Macs, down to the display size in the full-sized models. For a while it the appeared that the iPad was shaping up to become the future of Apple personal computers, and then the bottom fell out, at least temporarily, and there’s been a substantial resurgence in sales and interest in the MacBook Air and MacBook Pro series of notebooks.

Which makes the arrival of a new, 12-inch MacBook very timely. that Digitimes reported last week the MacBook is expected to make up 15-20 percent of Apple’s overall MacBook series device shipments of s in 2015, according to sources in the upstream panel supply chains.

Which makes the arrival of a new, 12-inch MacBook very timely. that Digitimes reported last week the MacBook is expected to make up 15-20 percent of Apple’s overall MacBook series device shipments of s in 2015, according to sources in the upstream panel supply chains.

A naming convention shuffle has been a bit confusing. Traditionally, Apple laptops designated just plain “MacBook” have been entry-level models, while the original MacBook Air was a premium-priced, albeit performance-compromised “image machine” with just lone USB and Micro-DVI I/O ports and a downsized MagSafe charge interface.

However, with the release of second-generation MacBook Airs in October, 2010, Apple shifted the MacBook Air somewhat downmarket, presumably to put more distance between it and the 13-inch MacBook Pro with Retina Display, which aside “from its higher-resolution panel was otherwise quite similar to the 13-inch MacBook Air in specification.

Since then the Mark II Airs have received five CPU and integrated graphics processor upgrades over the years, transitioning through Intel Penryn, Sandy Bridge, Ivy Bridge, Haswell, and Broadwell families of Core i5 and i7 processors, and Nvidia GeForce 320 M and Intel HD Graphics 3000, 4000, 5000, and 6000 series IGPUs. Battery life has also substantially improved, especially with the Haswell and Broadwell powered Airs, the current 13-inch model rated nominally at 12 hours runtime between charges, and the 11-incher at a still very respectable nine hours. Prices have also been cut, presumably to blunt competition from Windows Ultrabooks, and also thanks to amortization of design and development costs over a long production run.

Consequently the new MacBook’s market slotting very much resembles that of the original MacBook Air, with its premium pricing in today’s MacBook Pro territory (albeit $500 cheaper than the original $1,799 MacBook Air of 2008) while its performance, due to its works being jammy-packed into the smallest Mac laptop form factor ever, has exacted a toll on performance and connectivity, with less powerful versions of the Broadwell processor, MagSafe gone, and complete dependence on a single port supporting the new USB-C interface for charging, video out, and data I/O. We’ll have to see, but provisionally I have to say good luck with that, at least for anyone putting the new MacBook to work as a productivity platform.

On the other hand, if viewed as a bridge device combining roughly tablet-sized form factor (sort of; the new MacBook is still nearly twice the weight and thickness of an iPad Air 2) ,but with full Macintosh OS X software power and versatility, the new MacBook begins to look like a lot more powerful and capable tool than the iPad, and as such an intriguing potential alternative for those of us who have been putting the iPad into service for production and content creation tasks and trying to work around the many compromises that the iOS imposes. And if the iPad were to get USB-C, that would be viewed as a quantum progressive leap by many iPad users frustrated by the Apple tablet’s lack of connectivity and expandability.

Some have chided Apple for not copying Intel’s UltraBook lead and including touchscreen support, but I’m not among them, and am happy to swap touchscreens any day for good old trackpad and mouse support, especially in a unit with a physical keyboard and the display oriented vertically, rendering touchscreen manipulation both clumsy and unhealthy.

Meanwhile, the 11-inch and 13-inch MacBook Airs carry on with a Broadwell speed bump putting them several cuts above the new MacBook in performance terms, and priced substantially lower than the new MacBook, with a starting price spread between the 11-inch Air and 12-inch MacBook being $400, the base Air selling for $899, making it the lowest-priced Apple laptop in history so far. The lowball (at least in an Apple hardware context) MacBook Air pricing is of course in part facilitated by their being the last Mac laptops without a Retina grade ultra high resolution display. Personally, I find the 1440 x 900 panel in my 13-inch Haswell MacBook Air quite satisfactory for my needs, but if you just can’t manage without Retina resolution, it’ll cost more.

For me, the operative question has always been: “Can a smaller portable computer do everything I need to or am likely to want to do without objectionable compromise? The first Mac laptop I ever laid hands on — a PowerBook 165c — was an eye-opener more in terms of potential than  fact. The 165c with its 68030 silicon, murky, low resolution, passive matrix display, and maybe three hours’ real-world battery charge life was emphatically not a desktop challenger in the context of the time. The 68LC040 PowerBook 500 “Blackbird” series in 1995 was touted by some as “Quadra desktop power in a notebook,” — too blithely ignoring that “LC” qualifier in the processor designation that indicated the lack of a graphics co-processor, and the limitations of an 800 x 600 resolution 9-inch display (although you could drive an external monitor). Closer, but no cigar as yet.

fact. The 165c with its 68030 silicon, murky, low resolution, passive matrix display, and maybe three hours’ real-world battery charge life was emphatically not a desktop challenger in the context of the time. The 68LC040 PowerBook 500 “Blackbird” series in 1995 was touted by some as “Quadra desktop power in a notebook,” — too blithely ignoring that “LC” qualifier in the processor designation that indicated the lack of a graphics co-processor, and the limitations of an 800 x 600 resolution 9-inch display (although you could drive an external monitor). Closer, but no cigar as yet.

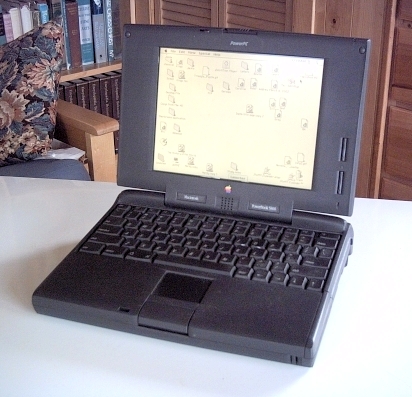

A watershed of sorts was the release of the PowerPC PowerBook 5300 in 1995, which was where I came aboard. The 5300’s 100 and 117 MHz 603e CPUs were still well short of real 604 desktop power, but I’d did incorporate a graphics co-processor, which sped things up substantially for  me moving up from a 68030 desktop Mac. Within an hour or so of opening the box, the 5300 had become my anchor production Mac, and I never looked back. It served me in that capacity for nearly three years, until I replaced it with a 233 MHz PowerBook G3 Series “WallStreet”, which I (and Macworld magazine in a cover story at the time) considered the first really legitimate Mac desktop challenger laptop, although others might draw the line at the immediately previous PowerBook 3400c or the externally similar but much more powerful original PowerBook 3500 G3 “Kanga.”

me moving up from a 68030 desktop Mac. Within an hour or so of opening the box, the 5300 had become my anchor production Mac, and I never looked back. It served me in that capacity for nearly three years, until I replaced it with a 233 MHz PowerBook G3 Series “WallStreet”, which I (and Macworld magazine in a cover story at the time) considered the first really legitimate Mac desktop challenger laptop, although others might draw the line at the immediately previous PowerBook 3400c or the externally similar but much more powerful original PowerBook 3500 G3 “Kanga.”

However, the WallStreet was the high water mark for Apple laptop connectivity and expandability, with two removable device/battery expansion bays and two PC Card slots, plus Serial, ADB, Infrared, telephone/modem, VGA,  S-Video, and SCSI high speed data I/O ports. You could have CD/DVD, floppy, SuperDrive removable media or an extra hard drive in the expansion bays, and update to USB and FireWire via PC Card adapters, and the CPU and RAM slots weren’t conveniently mounted on a processor daughtercard’ for easy and fast replacement or upgrading, All this versatility reinforced the WallStreet’s cred as a serious alternative to a desktop Mac for production content creation.

S-Video, and SCSI high speed data I/O ports. You could have CD/DVD, floppy, SuperDrive removable media or an extra hard drive in the expansion bays, and update to USB and FireWire via PC Card adapters, and the CPU and RAM slots weren’t conveniently mounted on a processor daughtercard’ for easy and fast replacement or upgrading, All this versatility reinforced the WallStreet’s cred as a serious alternative to a desktop Mac for production content creation.

Meanwhile, so-called “consumer” Mac laptops — usually smaller in form factor — had fewer connectivity and expandability features. The first small Apple notebook targeting the productivity-oriented user demographic was the 2001 12-inch Aluminum PowerBook G4, which started out with an 867  .MHz G4 CPU, but was incrementally upgraded to 1 GHz, 1.33 GHz, and 1.5 GHz, in most cases a bit less powerful than its larger 15-inch and 17-inch siblings, and it had an adequate but no more 1024 x 768 resolution display (same as the original iPad and iPad 2). However, there was enough power to satisfy many users who valued portability more than pure speed, and the 12-inch G4 PowerBook, which also had the distinction of being Apple’s last PowerPC Mac, is one of the fondest remembered and best-loved Mac laptops ever, with quite a few of them remaning in service long into the MacIntel era.

.MHz G4 CPU, but was incrementally upgraded to 1 GHz, 1.33 GHz, and 1.5 GHz, in most cases a bit less powerful than its larger 15-inch and 17-inch siblings, and it had an adequate but no more 1024 x 768 resolution display (same as the original iPad and iPad 2). However, there was enough power to satisfy many users who valued portability more than pure speed, and the 12-inch G4 PowerBook, which also had the distinction of being Apple’s last PowerPC Mac, is one of the fondest remembered and best-loved Mac laptops ever, with quite a few of them remaning in service long into the MacIntel era.

Today, I would say that the MacBook Air is the closest contemporary analog of the 12-inch PowerBook G4, and I expect that likewise current Air models will remain in service for many years to come.

As for the new MacBook, it remans to be seen. I think many of us have been gradually redefining what we need in a portable production platform. The late 2008 MacBook persuaded me that I could live without FireWire, and my 13-inch MacBook Air that I didn’t absolutely need an internal optical drive (although I still have an external one for when one is necessary.

And the iPad has taught me a lot about what I can and can not get along without, the latter category still including a Mac running OS X for doing things that the iOS and Apple tablet hardware just cannot do. Would the 12-inch MacBook bridge that capability gap? Maybe, but we’ll have to wait and see. I think it will take a revision or three before the new MacBook matures as a product enough (and perhaps drops in price like the MacBook Air has) to be fairly evaluated, and we decide whether we can live with just a single USB-C port.